- International Platform

- Content

Content

Silvan Omerzu – Visual Dramaturgy: The Artistic and Aesthetic Effects of Puppet Shows

Vesna Teržan

“Puppet art, after all, always takes place in two settings or scenes: the first is the isolated stage or the focused public space where the puppet show occurs; the second is the artistic aesthetic language in which the puppet art is expressed.” (1)

These words by Blaž Lukan best describe the true nature of puppet art. One of the people who are very conscious of the visual language of puppet shows is Silvan Omerzu. Omerzu is a Slovenian puppeteer in the finest sense of the word; a puppet designer, puppet engineer, and developer, director, dramaturge, set and costume designer, as well as a sculptor and illustrator. At the very start of his career, his primary roles included art and puppet design for puppet shows directed and dramaturgically edited by others. This is what he said about that time: “I felt the need for more authentic puppetry!” Soon, he realized that his ideas were easier to bring to life if he was also the director. When he was in charge of both direction and art design, he was better at solving visual problems and content-related issues alike, finding solutions for his directorial concepts, and bridging the gaps between the puppet’s buoyancy and the puppeteer’s stiffness. Omerzu has always allowed himself to be guided by visual dramaturgy. He seeks scenes that will work visually and fit with the show's message, knowing that puppets can be very effective, sometimes and often – though not always – more so than actors. Omerzu goes with scenes that work well with puppets and are made precisely as they should be, thereby adding layers for the full effect of the show on stage.

When designing puppets, Omerzu uses traditional materials in alternative ways. Interested in the coexistence of materials and the technology of puppets, he makes the puppets’ joints and mechanisms visible, just as he makes visible the material, which may be wood, polyester, paper, or metal. Omerzu uses the technology of the puppet to enhance the overall visual expression, exposing it, unlike “old-school aesthetes” who used to hide it. He often combines several types of puppets, from hand puppets and marionettes to Javanese rod puppets, Japanese Bunraku theatre, or automatons. In making puppets, Omerzu has had a long-lasting and successful collaboration with puppeteer and puppet engineer Žiga Lebar. What makes Omerzu’s puppet theatre special is his singular understanding of the puppet. He lets the audience feel, perceive and experience what many others conceal in order to create the illusion of reality. And yet his theatre is one of phantasms, illusions, and fiction.

The sunbeam falling on a girl puppet and her translucent, fragile body in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians (Hiša Marije pomočnice) evokes a different age a long time ago, the Neolithic, on an island in the Aegean Sea, where the sun lit up a male figure made of marble known today as the famed Harp Player. Now kept in the archaeological museum in Athens, the stylized statue was created around 2500 BC. While other Cycladic figurines and idols are known for their elementary, schematic outlines and flat, basic geometric shapes, the Harp Player shines in all its fullness and simple elegance. A similar simple elegance of a body made of marble, a true source of light and life for the Neolithic Harp Player, can be found in Omerzu’s wooden puppets. Simultaneously archaic and modern, their aesthetics at once Neolithic and contemporary, they speak with a visual language that is as grandiose as that of artworks from the ancient eras of history when humans understood nature and its shapes and were able to translate them into abstract representations of the intellectual and social values of a civilization. In his creative process, Omerzu draws on images from a “primordial memory”, creating simple shapes that only truly come to life and acquire a precise code of meaning once the puppet show begins. Watching them motionless is magic: even when they are sitting or standing still, a simple change of light in the room, a sunbeam, or an unexpected shadow falling on them may create the illusion of motion. At that moment, the puppets come to life – or seem to, to our senses. Light, especially natural sunlight, has always been one of the critical sources of life, in addition to water. Both light and water have brought everything to life, from the first forms of life on this planet to human creativity in ancient times (including Neolithic) or today, in the Anthropocene.

The sunbeam falling on a girl puppet and her translucent, fragile body in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians (Hiša Marije pomočnice) evokes a different age a long time ago, the Neolithic, on an island in the Aegean Sea, where the sun lit up a male figure made of marble known today as the famed Harp Player. Now kept in the archaeological museum in Athens, the stylized statue was created around 2500 BC. While other Cycladic figurines and idols are known for their elementary, schematic outlines and flat, basic geometric shapes, the Harp Player shines in all its fullness and simple elegance. A similar simple elegance of a body made of marble, a true source of light and life for the Neolithic Harp Player, can be found in Omerzu’s wooden puppets. Simultaneously archaic and modern, their aesthetics at once Neolithic and contemporary, they speak with a visual language that is as grandiose as that of artworks from the ancient eras of history when humans understood nature and its shapes and were able to translate them into abstract representations of the intellectual and social values of a civilization. In his creative process, Omerzu draws on images from a “primordial memory”, creating simple shapes that only truly come to life and acquire a precise code of meaning once the puppet show begins. Watching them motionless is magic: even when they are sitting or standing still, a simple change of light in the room, a sunbeam, or an unexpected shadow falling on them may create the illusion of motion. At that moment, the puppets come to life – or seem to, to our senses. Light, especially natural sunlight, has always been one of the critical sources of life, in addition to water. Both light and water have brought everything to life, from the first forms of life on this planet to human creativity in ancient times (including Neolithic) or today, in the Anthropocene.

Types of Puppets and their Mechanisms

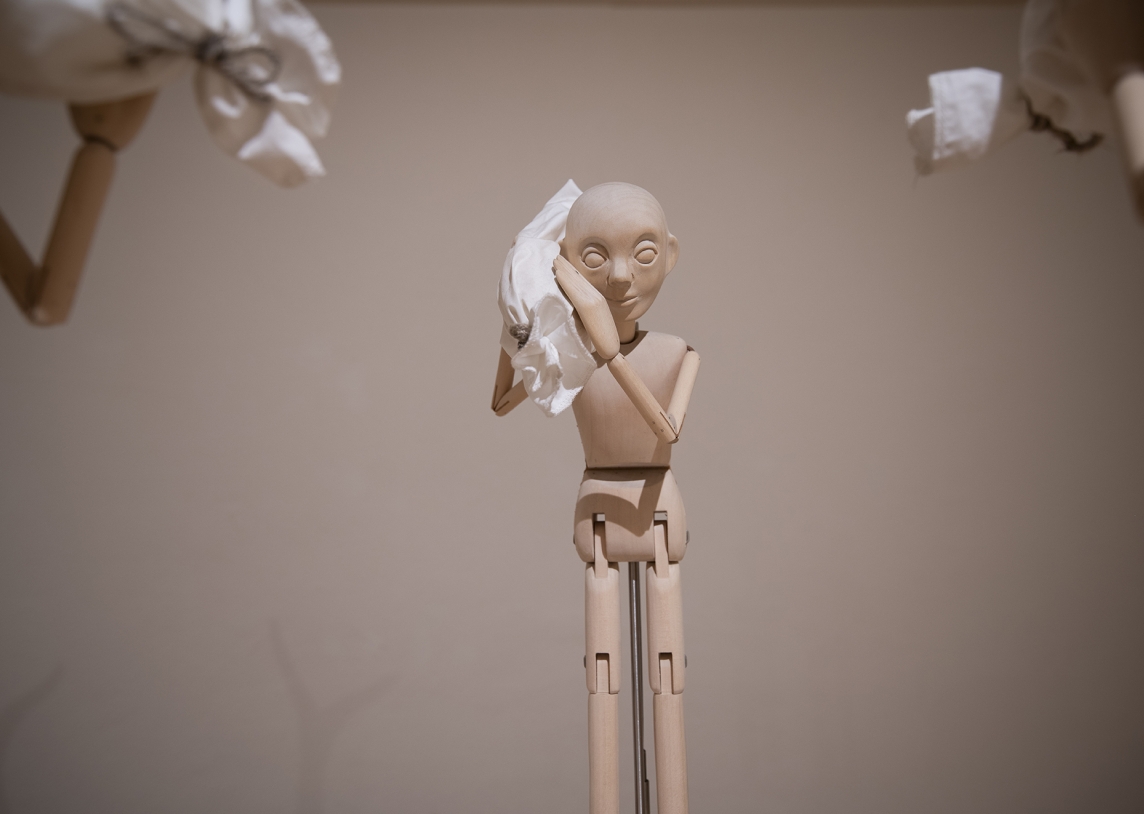

Since his first puppet shows, Omerzu has developed various types of puppets. The most prevalent type recently has been a medium-size wooden puppet with visible mechanisms, a standardized wooden torso with wooden limbs, and a schematic head with prominent, seemingly blind eyes, which come alive with the interaction of on-stage developments. Although confined to a set scheme and standard, each puppet.jpg) develops its own character. In their fragile ephemerality, the anthropomorphic girl puppets in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians (a 2008 production of the Mladinsko Theatre, Ljubljana, based on Ivan Cankar’s eponymous novel) are very different from their fully wooden fellows. Their visual aspects are exceptionally well planned: with heads made of papier-mâché, bodies of plexiglass, and arms and legs of wood with visible joints, they are very simple in shape but expressive in their sublime translucence. Freed of costumes and embellishment, they stand almost naked before us, all materials and mechanisms visible to us. At first glance, their faces all seem the same. And yet they aren’t. It is the smallest details, sometimes nothing more than a turn of the head, that sets them apart, and perhaps it is the different angles from which we are watching them that allow us to see the differences at all. These puppets, and The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians per se, marked a milestone in Omerzu's body of work. This was an unmatched production in Slovenian theatre in terms of stage composition, mise-en-scène, and the significance of individual visual elements for the story, but especially in terms of the variety of puppets. It was a full-blooded theatre production for adults in which puppets played the leading roles.

develops its own character. In their fragile ephemerality, the anthropomorphic girl puppets in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians (a 2008 production of the Mladinsko Theatre, Ljubljana, based on Ivan Cankar’s eponymous novel) are very different from their fully wooden fellows. Their visual aspects are exceptionally well planned: with heads made of papier-mâché, bodies of plexiglass, and arms and legs of wood with visible joints, they are very simple in shape but expressive in their sublime translucence. Freed of costumes and embellishment, they stand almost naked before us, all materials and mechanisms visible to us. At first glance, their faces all seem the same. And yet they aren’t. It is the smallest details, sometimes nothing more than a turn of the head, that sets them apart, and perhaps it is the different angles from which we are watching them that allow us to see the differences at all. These puppets, and The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians per se, marked a milestone in Omerzu's body of work. This was an unmatched production in Slovenian theatre in terms of stage composition, mise-en-scène, and the significance of individual visual elements for the story, but especially in terms of the variety of puppets. It was a full-blooded theatre production for adults in which puppets played the leading roles.

The third type of puppets seen in Omerzu's shows, including in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians, and in gallery exhibitions, is the head masks representing animals such as deer, ox or bull, fox, goat, pig, etc. The actor or puppeteer who puts on the animal head becomes a sort of Chimera, a wild, mysterious, even frightening creature, just like people who put on the "kurent" carnival costume to celebrate Shrovetide. Such puppet heads play a visible role in Kleist (Mladinsko Theatre, 2006), Words from the House of Karlstein (Besede iz hiše Karlstein, Maribor Puppet Theatre, 2017), Pinocchio (Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, 2015), where bird heads are used, and Ivana (Society of Slovene Composers, 2004), where they take the shape of fish. Automatons, the fourth type, have become one of Omezru’s preferred choices for protagonists in his shows (Forbidden Loves / Prepovedane ljubezni, Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, 2009; Krabat, Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, 2014), as well as for gallery exhibitions. Omerzu does not use automatons to get rid of puppeteers, but to add another dynamic dimension along with new layers of meaning. Their mechanical and simple movement introduces fresh angles to consider: Who are we, where do we come from, where are we going, who operates us?

frightening creature, just like people who put on the "kurent" carnival costume to celebrate Shrovetide. Such puppet heads play a visible role in Kleist (Mladinsko Theatre, 2006), Words from the House of Karlstein (Besede iz hiše Karlstein, Maribor Puppet Theatre, 2017), Pinocchio (Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, 2015), where bird heads are used, and Ivana (Society of Slovene Composers, 2004), where they take the shape of fish. Automatons, the fourth type, have become one of Omezru’s preferred choices for protagonists in his shows (Forbidden Loves / Prepovedane ljubezni, Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, 2009; Krabat, Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, 2014), as well as for gallery exhibitions. Omerzu does not use automatons to get rid of puppeteers, but to add another dynamic dimension along with new layers of meaning. Their mechanical and simple movement introduces fresh angles to consider: Who are we, where do we come from, where are we going, who operates us?

Table Scenes

In 2010, Omerzu put his work on display in the exhibition Automatons, Puppets, Actors in the International Centre of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana, literally populating the gallery space with puppets. Separated by doorways arranged in a straight line, the halls in the piano nobile of the historic Tivoli Castle, which saw its last architectural modifications in the mid-19th century, created a suitable layout for an “endless” table scene with small puppets and tables. In hushed tones, this fascinating exhibition told stories of the theatre and spoke about philosophical dilemmas to those willing to let their imagination run wild.

Is Difference the Gist of Similarity?

Tears, Omerzu’s second enthralling exhibition, was originally staged in 2006 in the former monastery church of the Božidar Jakac Art Museum in Kostanjevica na Krki (from where it traveled to the La Bellone Gallery, Brussels, and Casemate, Ljubljana Castle, in 2007). Historically and in terms of content, the display was based on the idea of tears measuring time. With their echoing sound, the drops falling from under the church arch into glass bowls enacted the moments that we steal from the eternity we are disappearing into, said Jure Mikuž in his text for the exhibition catalog. (3) At the same time, the teardrops evoked the rhythm of our limited time in this life running out, ever re-calculating the road that remains to be traveled and the moment of our inevitable departure. Mikuž likened the dripping tears to clepsydra, the ancient Greek water clock, “the one that steals water”, dictating short periods of the day and night but failing as all things fail to measure eternity. Visually (and technologically), the puppets in Kostanjevica were similar to those in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians, and yet very different in terms of their poses, spatial arrangement, and theological contemplation. In a way, Omerzu created a costume extravaganza, a spatial installation that was underpinned splendidly by the medieval church setting. This time, Omerzu covered the wooden puppets’ arms with sleeves, black for the male figures and pleated, lace-trimmed white ones for the female figures. With their shoulder and elbow joints are hidden in this way, the puppets, sitting on wooden cubes, still show their knee and ankle joints, the mechanisms indicating their pliability clearly visible. Meanwhile, the back of each puppet (its body wrapped in white gauze) revealed the cavity of the torso with the rails that allow the puppeteer to set it in motion. The church in Kostanjevica welcomed Omerzu’s puppets despite its challenging setting, in all its perfection. The shafts of light seeping through its Gothic windows brought the puppets to life, creating shadows that would play with their faces and hands, delivering a theatrical installation or a piece of spatial, puppet-based performance art.

based on the idea of tears measuring time. With their echoing sound, the drops falling from under the church arch into glass bowls enacted the moments that we steal from the eternity we are disappearing into, said Jure Mikuž in his text for the exhibition catalog. (3) At the same time, the teardrops evoked the rhythm of our limited time in this life running out, ever re-calculating the road that remains to be traveled and the moment of our inevitable departure. Mikuž likened the dripping tears to clepsydra, the ancient Greek water clock, “the one that steals water”, dictating short periods of the day and night but failing as all things fail to measure eternity. Visually (and technologically), the puppets in Kostanjevica were similar to those in The House of Our Lady, Help of Christians, and yet very different in terms of their poses, spatial arrangement, and theological contemplation. In a way, Omerzu created a costume extravaganza, a spatial installation that was underpinned splendidly by the medieval church setting. This time, Omerzu covered the wooden puppets’ arms with sleeves, black for the male figures and pleated, lace-trimmed white ones for the female figures. With their shoulder and elbow joints are hidden in this way, the puppets, sitting on wooden cubes, still show their knee and ankle joints, the mechanisms indicating their pliability clearly visible. Meanwhile, the back of each puppet (its body wrapped in white gauze) revealed the cavity of the torso with the rails that allow the puppeteer to set it in motion. The church in Kostanjevica welcomed Omerzu’s puppets despite its challenging setting, in all its perfection. The shafts of light seeping through its Gothic windows brought the puppets to life, creating shadows that would play with their faces and hands, delivering a theatrical installation or a piece of spatial, puppet-based performance art.

Start of the Creative Journey in the 1980s

After completing his studies at the then Pedagogical Academy, Ljubljana, Silvan Omerzu (1955) won a scholarship to study in Prague, where he specialized in puppet scenography and puppet design. Before he left for the Czech Republic in 1983, he had started working on a production and on shaping the visual course of his theatre. All he needed was affirmation. After visiting some Czech masters, he realized that those he valued most shared his way of thinking and his understanding of puppetry. Their shared view was reflected in his first art designs for puppet shows (Don Juan, 1995; King Ubu, 1999; The Little Altar of Don Cristobal, 2000; Woyzeck, 2001) directed by Jan Zakonjšek and produced by the Konj Puppet Theatre and co-producers. His early works also include the now legendary Make Me a Coffin for Him (Napravite mi zanj krsto, 1993). For this, Omerzu adapted a classical text that he found in the Czech Republic, turning it into a play that is both archaic and contemporary. If in a way, he traveled back in time, he used alternative aesthetics and approaches to mold an old story into a modern puppet show with traditional hand puppets. In his next show, Don Juan, Omerzu combined marionettes and Javanese puppets with automatons. In this period, he made grotesque, highly schematic puppets with painted faces, using a limited color palette of white, black, and red. The hand puppets’ characters matched their typically aggressive occupations, comical effects, and absurd situations characteristic of commedia dell’arte. Make Me a Coffin for Him went on to become a canonical piece, along with Don Juan (1995), King Ubu (1999), and Farewell, Prince (2001). Where social commentary is concerned, one can find it lined with comical undertones and striking grotesque elements, as well as a playfulness that seems naive and innocent but is brutally realistic at heart.

After completing his studies at the then Pedagogical Academy, Ljubljana, Silvan Omerzu (1955) won a scholarship to study in Prague, where he specialized in puppet scenography and puppet design. Before he left for the Czech Republic in 1983, he had started working on a production and on shaping the visual course of his theatre. All he needed was affirmation. After visiting some Czech masters, he realized that those he valued most shared his way of thinking and his understanding of puppetry. Their shared view was reflected in his first art designs for puppet shows (Don Juan, 1995; King Ubu, 1999; The Little Altar of Don Cristobal, 2000; Woyzeck, 2001) directed by Jan Zakonjšek and produced by the Konj Puppet Theatre and co-producers. His early works also include the now legendary Make Me a Coffin for Him (Napravite mi zanj krsto, 1993). For this, Omerzu adapted a classical text that he found in the Czech Republic, turning it into a play that is both archaic and contemporary. If in a way, he traveled back in time, he used alternative aesthetics and approaches to mold an old story into a modern puppet show with traditional hand puppets. In his next show, Don Juan, Omerzu combined marionettes and Javanese puppets with automatons. In this period, he made grotesque, highly schematic puppets with painted faces, using a limited color palette of white, black, and red. The hand puppets’ characters matched their typically aggressive occupations, comical effects, and absurd situations characteristic of commedia dell’arte. Make Me a Coffin for Him went on to become a canonical piece, along with Don Juan (1995), King Ubu (1999), and Farewell, Prince (2001). Where social commentary is concerned, one can find it lined with comical undertones and striking grotesque elements, as well as a playfulness that seems naive and innocent but is brutally realistic at heart.

.jpg) A milestone in terms of visual aesthetics came with The Sandman (2002) and continued with Councillor Krespel (2003). In The Sandman, Omerzu gave up colors entirely and let the basic materials “color” the show. He used a very diverse range of materials (paper to make the head, plastic pipes wrapped in gauze or fabric to construct the torso, wood to make the legs), making them ring in unison. In Councillor Krespel, the puppets had clean, colorless outlines, while wood, complete with skillful lighting design, gave the show a feel that was warmer and softer than his previous works. In 2006, Omerzu received the Prešeren Fund Award for Mystery of Life and Death (Misterij življenja in smrti), a trilogy consisting of Farewell, Prince; The Sandman; and Councillor Krespel. Therefore, in a way, he was awarded for the two markedly different creative periods, with an emphasis on The Sandman as an interim phase in his design. The three shows all draw from the same well in terms of content, but not in terms of aesthetics or visual styles. If Farewell, Prince belongs to the creative period of macabre puppets, when he still used colors, The Sandman and Councillor Krespel are from "Omerzu's new era" of minimalist and more elegant puppets. As a result, the awarded trilogy is made up of two artistically and aesthetically wholly different styles. Although the three shows are similar in terms of genre, drawing on fantasy on the one hand and the eeriness of the moment on the other, they could hardly have been more different when it comes to their artistic styles.

A milestone in terms of visual aesthetics came with The Sandman (2002) and continued with Councillor Krespel (2003). In The Sandman, Omerzu gave up colors entirely and let the basic materials “color” the show. He used a very diverse range of materials (paper to make the head, plastic pipes wrapped in gauze or fabric to construct the torso, wood to make the legs), making them ring in unison. In Councillor Krespel, the puppets had clean, colorless outlines, while wood, complete with skillful lighting design, gave the show a feel that was warmer and softer than his previous works. In 2006, Omerzu received the Prešeren Fund Award for Mystery of Life and Death (Misterij življenja in smrti), a trilogy consisting of Farewell, Prince; The Sandman; and Councillor Krespel. Therefore, in a way, he was awarded for the two markedly different creative periods, with an emphasis on The Sandman as an interim phase in his design. The three shows all draw from the same well in terms of content, but not in terms of aesthetics or visual styles. If Farewell, Prince belongs to the creative period of macabre puppets, when he still used colors, The Sandman and Councillor Krespel are from "Omerzu's new era" of minimalist and more elegant puppets. As a result, the awarded trilogy is made up of two artistically and aesthetically wholly different styles. Although the three shows are similar in terms of genre, drawing on fantasy on the one hand and the eeriness of the moment on the other, they could hardly have been more different when it comes to their artistic styles.

Visual Dramaturgy

The significance of visual dramaturgy seems to be contemplated primarily by so-called complete “auteurs” such as Omerzu. For him, visual dramaturgy is key – an essential element of any puppet show (or any piece of theatre in general). To create a total work of art in puppetry, one in which all the vital elements of a production come together to form a harmonious whole – art design, puppet design and making, direction, technology, set design, dramaturgy, puppet animation and performance, and finally, music or sound – one has to follow a visual dramaturgy. This is the key to success. Puppet shows have always been and always will be a feast for the eyes, and without the artistic aspect, no show seems to be possible. There is no puppet theatre without visual elements, regardless of how minimalist its art design is; it is always there as the first thing that catches our eye.

Visual dramaturgy is a means to create dramaturgical suspense in theatre. It adds to the spectacular effect, which is always welcome in theatre one way or the other. Omerzu’s approach is to build tension and heighten the emotions, and to do this in his unique rhythm. Informed by the contemplation of the ultimate things in life, his highly personal visual poetics ultimately boils down to the fine line between life and death. In simplified terms, the two messages of his shows – those he directs and those that only feature his art design – are doubt and the need to reconsider the meaning of life and the consequences of our actions. Be it shows for children or adults, the one element that underlies them all is a sober reflection on existence and meaning. Incidentally, Omerzu is one of the few puppet artists (by which we mean the creators of art designs for puppet theatre productions, puppet makers, dramaturges, and directors) who develop puppet shows for adults. This is far from a common phenomenon in Slovenia, the prevalent belief being that puppets are primarily meant for children. This popular opinion indicates a lack of knowledge of the history of puppet art. That is part of the reason why the year 1993 was so significant for the puppet scene in Slovenia: it was then that Silvan Omerzu and Jan Zakonjšek established the Konj Puppet Theatre, where they made their ideas of puppetry a reality, and where Omerzu began developing his unique poetics. (4) In the early 1990s, the Konj Puppet Theatre introduced some new features into Slovenian puppet theatre, while Omerzu pioneered several technological innovations and stunned the scene with a new aesthetic. In his straightforward yet expressive style, the theatre staged a repertoire of highbrow plays. The bitter black humor that emerged at the time has remained a staple of Omerzu’s shows ever since.

For the shows he worked on in the past two decades, Omerzu has usually been the director, visual designer, and puppet designer. His latest shows include Pinocchio at the Ljubljana Puppet Theatre (2015), a stylistic continuation of his use of head masks and wooden puppets with clean lines, and Salto Mortale at the Maribor Puppet Theatre (2012), where he seemed to return to the aesthetic expression of the 1990s, building on three basic colors – white, black and red – and schematic bodies. The lower limbs were still made of wood, and their joints visible; the head colored white, with eyes embossed in its forehead; the mouth and moveable lower jaw reaching from one end of the face to the other, the nose protruding from the white face, vaguely reminiscent of the grotesque expressions of his early puppets from the “post-Czech” period. One feels as though they are witnessing a synthesis that promises new visual surprises.

In the last couple of years, Omerzu has worked on a couple of high-profile exhibitions. The first one was Ivan Cankar and Europe at Cankarjev dom in Ljubljana in 2018, which he designed and mounted in collaboration with the architect Katarina Štok Pretnar. For the display, he made small figurines of the writer, as well as a large wooden head, a kind of an automaton sticking its tongue out and moving its eyes, all as part of a presentation of Cankar’s life and work. Omerzu also designed a haunting set of puppets (2018) based on Cankar’s sketch story Captain Sir (Gospod stotnik). The wooden structure symbolized the captain’s wagon carrying puppets arranged in military ranking order: soldiers, the wounded, two drummers, and automatons. As the entire structure moved, small shadow puppets danced the dance of death on the gallery walls. What astonishes the audience about Omerzu’s spatial installations time and time again is the animation potential of stationary puppets, placed in a space and lit up in such a way that they create a powerful experience.

with the architect Katarina Štok Pretnar. For the display, he made small figurines of the writer, as well as a large wooden head, a kind of an automaton sticking its tongue out and moving its eyes, all as part of a presentation of Cankar’s life and work. Omerzu also designed a haunting set of puppets (2018) based on Cankar’s sketch story Captain Sir (Gospod stotnik). The wooden structure symbolized the captain’s wagon carrying puppets arranged in military ranking order: soldiers, the wounded, two drummers, and automatons. As the entire structure moved, small shadow puppets danced the dance of death on the gallery walls. What astonishes the audience about Omerzu’s spatial installations time and time again is the animation potential of stationary puppets, placed in a space and lit up in such a way that they create a powerful experience.

His latest two exhibitions were retrospectives. The larger of the two was held at the Božidar Jakac Art Museum in Kostanjevica na Krki in 2020/21, where Omerzu exhibited large wooden puppets made for shows and some other exhibitions after 2002. The second one, at Rajhenburg Castle in Brestanica, displayed his earlier work from the 1990s: the grotesque, rowdy hand puppets from the "post-Czech" period. Both exhibitions provided a good insight into Omerzu's contribution to puppet art in Slovenia.

Silvan Omerzu is undoubtedly sui generis in Slovenian (and European) theatre, an extraordinary, unique, and exciting artist. His versatile works for theatre productions, whose puppets often had a second life in galleries, cannot be categorized as theatre artifacts alone; as artworks, they also form a vital part of Slovenian visual art.

***

References:

1. Lukan, B. Omerzu's Puppets and Their Performativity, tr. Rawley Grau, catalog for the exhibition ‘Silvan Omerzu, Automatons, Puppets, Actors’, Ljubljana: MGLC, 2010, p. 10.

2. Ibid., p. 20.

3. Mikuž, J. … in hac lacrimarum valle, catalogue for the exhibition ‘Silvan Omerzu, Tears’, Kostanjevica na Krki: Galerija Božidar Jakac, 2006.

4. Orel, B. The Mark of Horse, Silvan Omerzu and the Konj Theatre Ljubljana: Društvo lutkovnih ustvarjalcev and Ustanova lutkovnih ustvarjalcev, 2005.

This publication is written in the context of the project "European Contemporary Puppetry Critical Platform"