- International Platform

- Content

Content

The Unbearable Freedom of Associative Thinking

Author: Maša Radi Buh

The last three biennial editions have indicated two strong artistic currents in puppet theatre. One is on the traditional trajectory of conventional puppetry, with the puppet still the leading protagonist of the production and the key agent of the plot, while the other is contemporary puppetry, a current questioning the puppet and juxtaposing it with other equivalent elements of the show. Any biennial selection made by an arts festival curator can go different ways, depending on how the specific curator perceives their role. In its official competition, the 11th biennial in Maribor replaced the paradigm of selecting the best productions of the past two years, for one that categorises the multitude of the existing practices (not necessarily very well executed but with a good concept) and brings puppetry in Slovenia in touch with deliberations concerning the contemporary puppetry trends seen at international festivals. The most daring choice for the festival may have been Vlado R. Gotvan’s The Last Temptation. Although by no means developed with the intention of exploring puppetry, the production immediately avoided any potential conceptual assumptions and premises that inevitably arise with one’s idea of what a puppet is. In the end, it put this question to the loyal puppetry audience.

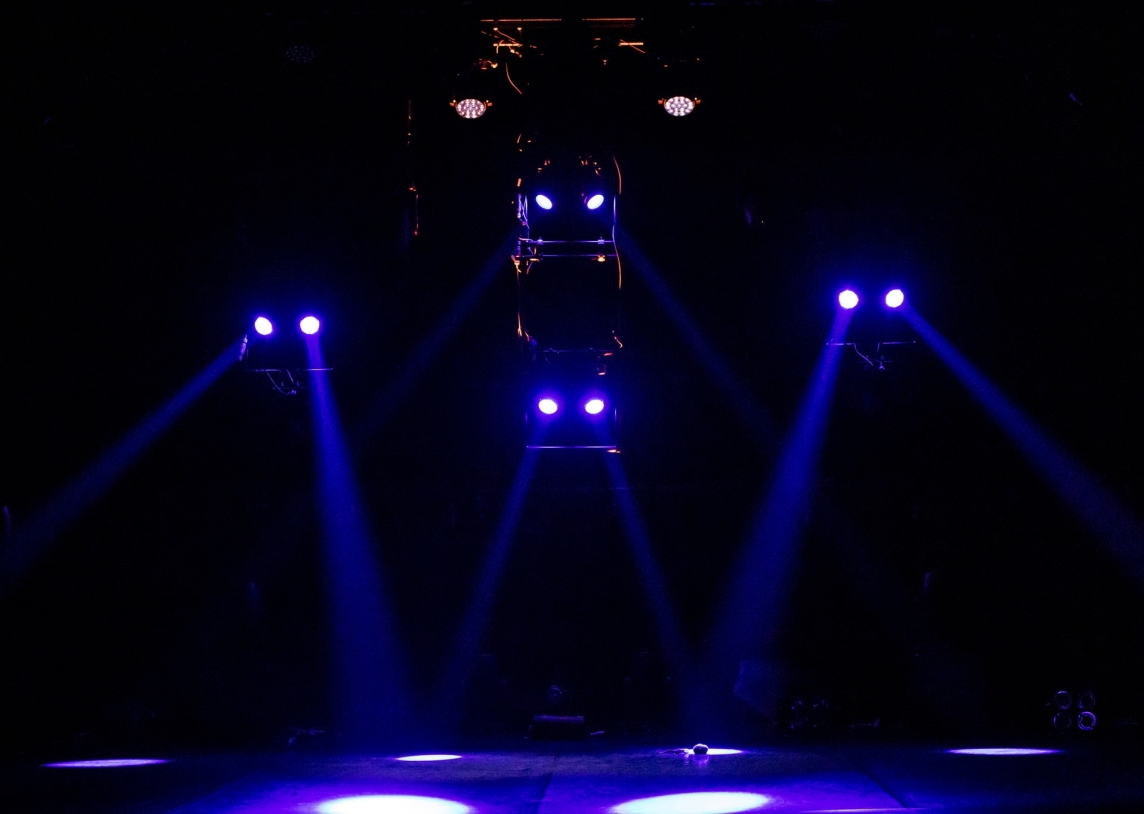

The Last Temptation is a feature-length collage of light and sound focusing primarily on the audience’s phenomenological experience. The introductory video is followed by daily life videos in random order, from animals to an excavator, with an acoustic landscape underlying the images. The carefully processed sound of the excavator pushing through a pile of dirt, nature and animals; all this produces a clean, clear sound effect in the excellent acoustics of Kino Šiška’s Katedrala Hall. As the performance progresses, the human voice is added to this acoustic element, with folk songs sung live into the microphone by Manca Trampuš and Zvezdana Novaković. The way they are positioned in the space lit up when singing and otherwise concealed, creates the only diversion of the spectator’s attention from the stage, where the light show takes place throughout the rest of the performance. Therefore, their remote position at a breakneck angle shapes the dramaturgy of the gaze, the leading protagonist of The Last Temptation, shaking it up. As Gotvan builds his show primarily by directing the elements of stage lighting – thereby following on from Luftbalett, his previous work that used the same concept – the pivotal information conveyed to the audience is visual. The atmospheric lighting not only keeps changing in terms of the colour or intensity of light but also combines with moving elements of stage lighting. Programmed by the director and lighting designer, their moving pointed beams skim, scour and scan the space.

The hour-long light show explores human presence and absence in theatre. Now a very popular topic in academia and art internationally, it creates space for reflection on the hierarchies arising from human perception of oneself as a unique and most highly developed (living) being on the planet. The Last Temptation is in no way genuinely free from human presence. On the one hand, both singers are there, even if to emphasise the absence of the human body on stage. On the other hand, even when it is an object that takes centre stage and when it is the objectness of stage lighting elements that we are looking at, they are still controlled by humans and their decisions.

Nevertheless, Vlado R. Gotvan blazes a unique trail in Slovenia’s performing arts, consciously resisting the historical pressure of the dramatic narrative arc, an old convention, and the still prevalent dramatic types of theatre in the region. The production refuses to succumb to the need for a meaning, idea, or common thread. The only elements one can resort to for any subject matter include the introductory video collage and song lyrics, although the production clarifies that it is undesirable, hence pointless, to interpret them in connection to lighting.

The lack of such tangible, interpretatively powerful elements, still ubiquitous in Slovenian theatre but increasingly rejected in some contemporary dance practices, frees the audience of a fixed gaze. The production’s dramaturgy is the dramaturgy of one’s associative thinking, which leaves the spectator alone with their own thoughts, imagination, and commitment. The show maneuvers between meditation, experience, and dread, for too much freedom without restrictions is universally known to cause more anxiety than clear instructions and boundaries. This is both its advantage and potentially its weakness: as such, the production is made and intended for a small target audience that feel no need or desire for meaning, narrative, or idea. Instead, they are happy to have a meditative experience featuring visual and audio elements where reason can take a break from weaving semantic networks. However, such a production requires a second type of freedom: not only from humans but also from the deeply rooted conventions of what theatre is supposed to be.

Against the backdrop of the Biennial of Puppetry Artists and the discussions in contemporary puppetry about the types of objects that may transform into puppets, The Last Temptation foregrounds the dilemma of what is human and what is puppetry or, better yet, of the human element in puppetry. The pre-programmed animation of the light extravaganza raises the question of whether we perceive the moving spotlights as animated objects that go beyond the sheer relationship between the programmer and the object. In any production, lighting elements are animated by humans, even if through pre-set algorithms that ultimately execute the action autonomously. Any programme is invariably informed by human decisions. That said, lighting elements may be perceived as puppets or animated objects. This happens when they come alive before our eyes when we detect attributes of life or a soul in them. The questions that remain revolve around under what circumstance we habitually recognise such objects as alive and what properties of movement and behaviour they must possess for this to happen. Based on The Last Temptation as one of the productions selected for the biennial, I would argue that an object is perceived as a puppet when we detect in it a quality of movement that fits with our idea of living beings similar to humans. Just as the movement of a box has to mirror familiar gestures from the vocabulary of human or animal body movement in order to "come to life", the same is true for other animated objects such as robots, lights, etc. Even if we, humans, are capable of pulling away from exclusively human images, what we truly search for in a puppet and animation are even the faintest traces of our own reflections. As an audience, we are (still) incapable of recognising "life" when it comes with no identifiable human properties. At the end of The Last Temptation, we are left with an existential question: What or whom do we refer to as being alive? Or, more importantly, what or whom don’t we?

***

At the 11th Biennial of Puppetry Artists of Slovenia, the author saw a version of The Last Temptation that included additional material and was titled Blind Interactivity.

This publication is written in the context of the project "European Contemporary Puppetry Critical Platform"