- International Platform

- Content

Content

Well, that's not really going anywhere...

Author: Tjaša Breznik

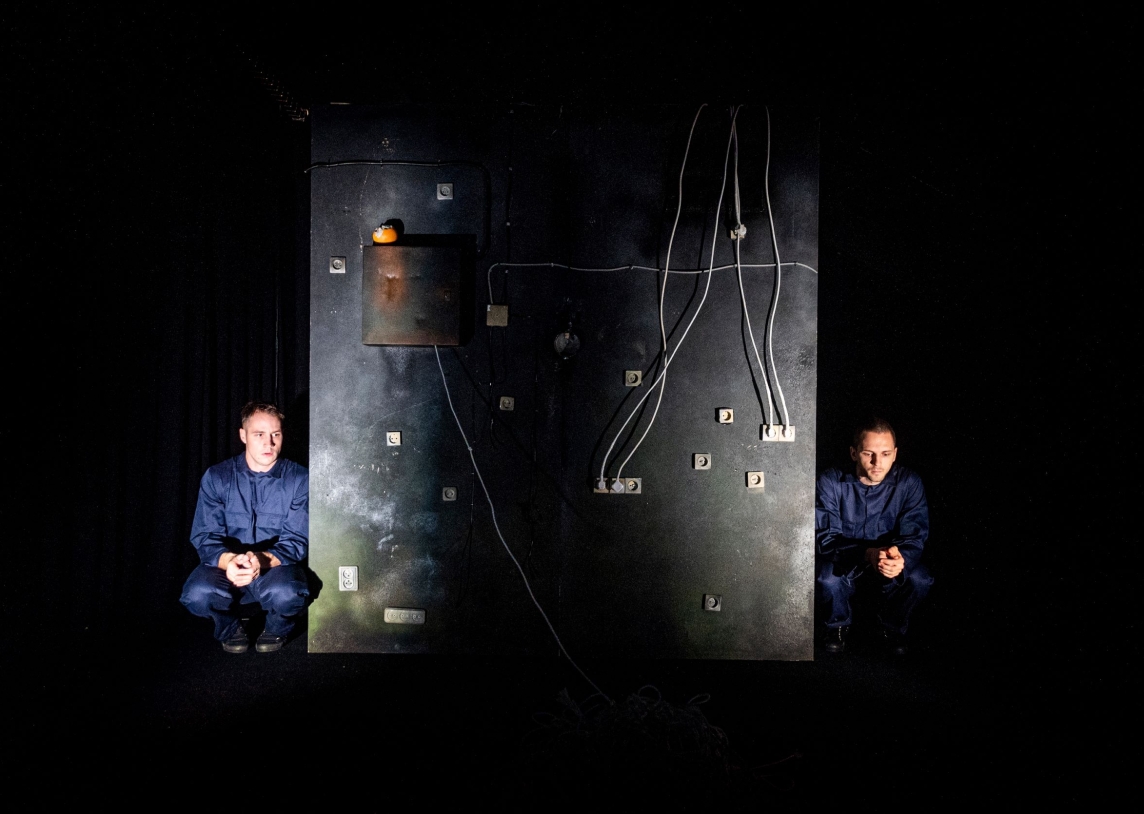

And we got electricity! This miracle of self-generation that we now take completely for granted. The realisation that we are always equipped with electricity and the benefits it brings only come in its absence. And power outages do not happen very often either, and when they do, they are immediately tamed by the workers who specialise in electricity. But what would happen if electricity and the objects connected to it got out of control? What would happen if cables and sockets went their own way? Judging by performance The Socket of the Vilnius Theatre “Lėlė”, even the electricians are not entirely comfortable in such a situation. Or perhaps they are even amused by the resulting electrical chaos, because at last the tension rises and they can communicate with the objects of their expertise.

The characters of the two electricians are poorly defined in the performance. Their role is merely to assist in the dramatic blackout. Their status is not clearly defined, which would have added a comic touch to their actions in a world that does not lack absurdity. In a performance where the object is central, the interaction between people and objects is important as they begin to play with people and make them (endearingly) uncomfortable. So the human characters are not unimportant as they react like an extension of the audience to the suddenly alive cables. The interaction between the two human characters is also unconvincing. The impression is that they are blindly following a script, without any emotional input. The bodies are somehow immobile when the actors come into contact with each other, giving the uncomfortable feeling of just performing. This is strongly felt during the simulated quasi-brawl that was created for nothing. So the reasons for the stage actions seem to be void, even pointless. It is unclear why there is this sudden contact between the actors, it just happens. “It just happens” is an apt description for a hopping of content that nevertheless feeds on a single connecting element: objects connected by electrical lines, mostly cables and sockets.

The scenes are fragmented in terms of content and it would be difficult to say that they follow a particular thread. Each scene is its own story. An animator and an object meet and, due to their “fluidity”, create a play between them that is the result of an association. The same object can be animated in two different scenes in completely different ways and thus practically become a completely different object. The creators use the objects connected to the electric lines in many different ways, following the principle of the “unknown object”. This principle leads us to see the object as something other than what it really is. So it says that we have to use the object as what it is not. In this way, the object actually becomes what it is not. By intelligently changing its function, the way we look at it also changes, because it becomes a multi-faceted thing that opens up a universe of new narrative possibilities.

The performance is full of playful experiments that go hand in hand with the nonsense that is painted on like snowflakes but is thoroughly interesting. Sometimes the power of absurdity in a scene makes us want to flip the scene in front of us like a TV channel, or even better, flip a switch, turn off the lights, turn them back on and find ourselves in a new story. Our wish is granted. The persistent tugging on the power box cable and the agonising trance that accompanies it are interrupted by a dancing belly with a power socket instead of a belly button in the middle of its body. Then comes the blissful cut, the release. The tension of waiting, caused by the itching curiosity of what will be hidden at the end of the endless rope, is broken. We are neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with the outcome. The performance is driven by a coincidence that is better explained by the word randomness, and which the audience does not want to understand. This is the kind of performance that does not give a damn about our (lack of) understanding. The makers play with the objects as they please, believing that each of the audience will find a scene that appeals to them. It is as if we are offered a handful of sweets and we take one of them, sweet or sour. It just depends on how we feel at that moment.

The music does not support the experimental attitude of the production, because its calmness, its melancholy and its almost superfluous nature immerse us in a dispassionate mood. In the creative solutions, in the moments when the animation develops in an original way, the music pushes it to the ground with its unplayfulness. It is undynamic: very aquatic, quiet, atmospheric or turns into a punctual drumming to illustrate the fall of the cable on the hard floor. Perhaps it is this resemblance to thunder that wakes up viewers who have already succumbed to the monotonous musical sounds. Cables that move like animals, like a group of geese or ducks, are very endearing as they try to escape their huddled lives. At the same time, they cannot escape the tempting socket that relentlessly lures them to it. At this point, the music could have emphasised the observed moment of humanity in the puppets and made the effect of this humorous conceit even more pervasive.

In the performance, the literal personification of the electric wires occurs when a part of the human body appears on the other side of the wall, behind the electric box, from which the wires “grow”. This could be the navel mentioned earlier, or simply the commanding hands that intertwine and tangle with the fingers, casually reclaiming the objects of electrical experience. The space behind the wall is alive, unknown, threatening, strange. None of the attitudes between the hands and the actors, or even between the animators, are definitively resolved. One can surmise that the performance is in a creative phase, a time of playing with possibilities. The phase of immaturity, of the interpenetration of several ideas, i.e. of free play, may well be respectable, but the performance in question is at times still trying to establish the germ of a story. In addition to this abrupt content, the audience encounters further questions regarding the relationship between these characters in the example of the final scene in which three people drink tea. Are all the actors persons at all? Until recently, the actress embodied the electrical wiring. When did she cross the boundary of the electric box? The ending pointlessly tries to make sense of something that is completely unnecessary.

The Socket nevertheless serves us a pinch of magic, a good measure of indeterminacy and vividness of technological, but nowadays quite basic, electrical achievements. It moves away from the primarily utilitarian function of the electrical installation and gives it a life of its own. In this way, the other side of the logical, namely the magical, is established. Objects that have always worked become playful and inexplicable. So man plays with practically everything, but the homo ludens in us does not fade away, but is always on the lookout for new connections, new sockets into which he can plant his thoughts and introduce a new idea.

This publication is written in the context of the project "European Contemporary Puppetry Critical Platform"